Early on in the research for The White Devil’s Daughters, I learned about a horrific aftermath to the story I was writing. My focus was on a group of women residents and staffers of a historic safe house who fought sex slavery at the turn of the 20th century. One day, while sifting through case files with the home’s retired executive director, she suddenly turned to me and asked, do you know about Dick Wichman?

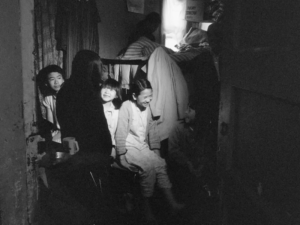

I didn’t. So, in a somber tone, she told me the chilling story of a sexual predator who, for decades later in the 20th century, abused boys in the very same place where my story was set –the safe house in San Francisco’s Chinatown that my characters had established in the 1870s to protect girls and women.

I felt shock – and soon realized I was facing a challenge. How should I handle the monster in the basement – which was, literally, where the abuse took place? To include him in a book about heroic women could overshadow their story.

The home’s retired director, a woman named Doreen Der-McLeod, gave me fair warning. Before I ventured too far down the path of telling the stories of the brave women who’d fought human trafficking and slavery at the turn of the 20th century, she wanted to make sure that I understood the full horror of what occurred decades after the women had left the home.

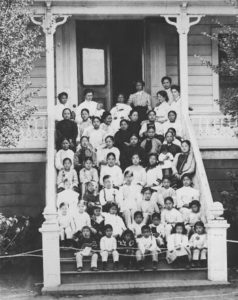

I’d planned to begin my book in 1874, when a group of churchwomen founded a safe house for vulnerable women. Thousands of mostly Chinese girls and women took shelter there over seven decades, including several who went on to live remarkable lives. The home’s long-serving director was Donaldina Cameron, and the home was eventually renamed Cameron House in her honor. The book would end with her retirement in the late 1930s.

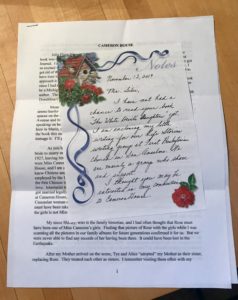

The person recruited to Cameron House after the women’s’ project had ended was the Rev. F.S. “Dick” Wichman. He became the institution’s first male director, and he created a thriving program for Chinatown’s youth. But he also turned what had been a sanctuary for girls and women into a profoundly unsafe place for boys and young men. As the home’s director from 1947-1977, Wichman was a pedophile who preyed on vulnerable boys. (Both Cameron House and the Presbyterian Church have publicly acknowledged and apologized for his abuse.)

F.S. Wichman (left) and Donaldina Cameron (right), photo courtesy of Cameron House

By one count, there are 40 known victims of Wichman – all of whom he raped or molested when they were boys, and all Chinese. Some estimate the actual number may be in the hundreds. His predations defiled the dreams of Cameron and many others who devoted their lives to fighting sexual exploitation.

In researching and writing The White Devil’s Daughters, I decided to end my story before the period of Wichman’s abuse – ignoring what would happen in the future. I dealt with Wichman in a single paragraph in the acknowledgments. I didn’t want his story to undermine the accomplishments of the women I was writing about.

But it became impossible for me to continue to ignore Wichman’s decades of abuse after The White Devil’s Daughters was published. His story continued to hang over Cameron House like a dark cloud. As the Rev. Gregory L. Chan later described Cameron House, where he’d served as the board chairman and interim executive director, “the place felt like the Bates Motel in Psycho. We had not cleaned up the shrouded energy…”

In the summer of 2019, Cameron House, along with the Chinese Historical Society of America, hosted a large event to discuss The White Devil’s Daughters. Hundreds of people attended, many of whom had long ties to Cameron House and to Wichman.

During this event, and in private conversations afterwards, Wichman’s name arose – again and again. It became clear to me that there remained a crucial, second story to be told about his era at Cameron House. Yet I was reluctant to tackle it. I knew the reporting would force me to dive into the dynamics of clergy sexual abuse – an area that frightened and disturbed me.

It was a Facebook post about a film in the summer of 2020 that finally tipped the scale. A short documentary had been released about Cameron House’s long effort to acknowledge Wichman’s abuse and embark on a long journey of healing. More than a hundred people commented on it in a heartfelt outpouring of solidarity. Elaine Chan-Scherer, a former Cameron House staffer, who played a crucial role in bringing the abuse to light as a whistleblower, tagged me in her post. Because of the release of the film, I realized this was the moment to write about Wichman, who died in 2007. This was the right moment because the community’s healing process was nearly complete.

Wichman’s three decades at Cameron House were antithetical to the spirit that had guided the project of providing a safe place for vulnerable girls and women. It felt right to follow up my book with a detailed investigation of his time at Cameron House.

As a result, my expose, titled “The Safe Place That Became Unsafe,” about Wichman’s era of abuse and the community’s efforts to heal from it, was published in the Winter, 2021 issue of The Journal of Alta California. That gave me the chance to tell the story of the monster in the basement. While there are probably even more stories to be told about the home, they don’t all need to be told in one telling.

***

This essay was adapted for one first published in The Biographer’s Craft, with thanks to its editor Michael Burgan.