An Afternoon with a U.S. Poet Laureate

As a long-time reporter, I’ve met a lot of people. Perhaps the most inspiring was our recent U.S. Poet Laureate, William S. Merwin.

For decades, Merwin has lived off the grid in Hawai‘i. To reach his home, I turned off Maui’s fabled Hana Highway, down a single lane edged with red volcanic soil. About a quarter of a mile from steep cliffs dropping to the sea, the foliage began to grow thick. Rustic wire fencing strained to hold back arching fronds and tropical blooms. His 19-acre palm forest seemed like it was trying to swallow the lane.

There was no hint that this was the home of a celebrated writer – just a swinging metal gate secured with chain – the same kind used by neighbors raising cows and chickens. A sign on a nearby property reads “Respect the keiki,” the Hawaiian word for children.

Just beyond the gate was a modest carport. Mounted on its roof were solar panels which supply all of the home’s power. Several hundred yards beyond the carport, down an unpaved track, was the Merwin’s self-sufficient home, which seemed to disappear into the jungle.

Paula, William’s wife, met us on the outside lanai, where we slipped our shoes off and entered. My first impression of the house was that it was like a Polynesian longboat – a rectangular floor plan, with wood on the ceilings and darkly oiled eucalyptus wood floors.

Books were everywhere — books on gardening right at the entrance, cookbooks in the bathroom, an entire extra room downstairs devoted to books, whose shelves overflowed, leaving volumes stacked on the floor.

We sat in what the Merwins call their breakfast lanai – a covered porch that leads from the kitchen looking directly out onto the palm forest. That’s where the couple has their breakfast and where they spend time with visitors. Unlike the darker living room, it is light-filled and hospitable, even during torrential downpours.

They’d lit incense to keep the mosquitos away and William and I sat on the lanai at the beginning of our visit. Our talk meandered. I could sense he was sizing me up and trying to decide whether he’d cut the visit short or spend just the allocated time with me. He ended up spending more than four hours with me – a gift I’ll never forget.

What struck me most was his incredible mind. As we rambled through his forest, he was able to pull up the Latin names of obscure palms, remembering where he got them, as well as often funny stories about the genus or how he got the plants as well. He’s 83, but possesses a sharper intellect than perhaps anyone I’ve ever met.

He was also very kind. I’d wrecked my knee in a ski accident and recently had reconstructive surgery to fix it. William was very thoughtful about my knee, providing me with a bamboo walking stick for our hike around the property where he’s planted hundreds and hundreds of palms.

We’d walked for about half an hour when he paused at the greenhouse where he grows palms from seed. He stopped to quote a 14th century Japanese Zen master whose poetry he’d helped translate on the different reasons why people create gardens. He also quoted Robert Frost grumpily commenting, after a radio interview, that journalists somehow assumed that writers cared about being in the press, confessing his exhaustion with being in the public eye as poet laureate.

He also spoke of how he’d become involved in Hawaiian activism (protesting the bombing of the island of Kaho’olawe ) but added that some of the activists had gotten violent and didn’t want haoles (foreigners or people who are not native Hawaiians) involved, so he and Paula had dropped out. He had also studied the Hawaiian language and had an appreciation of chant and oli (a chant that was not danced to).

We discovered we were both admirers of Hawaiian language scholar Puakea Nogelmeier, and that William had been introduced by Puakea to his mentor Theodore Kelsey in the hospital, shortly before Kelsey’s death. He also told me stories of how botanists and other plant enthusiasts had sent him palm seeds from around the world.

William struck me as someone who had truly given something meaningful to his adopted home of Hawai‘i – rather than being like the migrating kōlea, a bird from the mainland that gorged on the most luscious berries and choicest fruits from the islands, then took off again for the mainland. The kōlea, like so many other visitors, took from Hawai‘i without giving back.

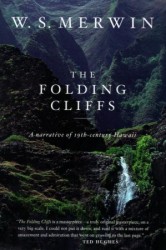

But William and Paula had turned agricultural wasteland into a beautiful forest. He’d also contributed to a deeper understanding of Hawai‘i an history through his book, The Folding Cliffs, which in poetic language grappled with the same tragic history that I’ve been immersed in for the past few years.

I’m deeply grateful to my editors at the Wall Street Journal for giving me a reason to meet William and Paula. In honor of National Poetry Month, here’s a line from one of William’s best-known poems titled “Place.”

“On the last day of the world / I would want to plant a tree.”

To learn more about William and the palm forest that he and Paula have created, visit the Merwin Conservancy’s website.

My daughter writes poetry too and likes it when I send her interesting poems that come my way. After reading your post, I’ve sent her on of Merwin’s.