At opening night of the 2017 Tennessee Williams Festival in New Orleans, I met a librarian who also happens to be a champion ham kicker.

She shimmied her way onto the stage of Le Petit Theatre du Vieux Carre in New Orleans in a sparkly black top and full-length skirt. Channeling the spirit of one of her heroes, Mae West, she delivered a lively and ribald talk on a subject that has fascinated her for some 35 years: the “blue books” of Storyville, the red-light district of New Orleans that flourished from 1897-1917. The “blue books” were guidebooks to the prostitutes and brothels in the district

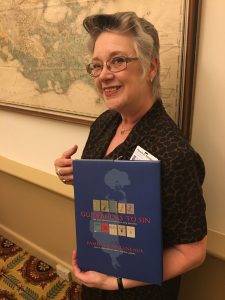

The ham-kicking librarian wears spectacles and is nearing retirement. Her name is Pamela D. Arceneaux. She is the senior librarian and curator for rare books of The Historic New Orleans Collection, a non-profit dedicated to preserving the culture and history of New Orleans and the Gulf South. “Lookin’ at me, I don’t look like someone who talks about whores,” she deadpanned when we met a few days after the event, at her workplace, the hushed, wood-paneled Williams Research Center in the French Quarter.

The blue books that she loves carried advertisements for such brands as Budweiser, Veuve Clicquot, and Mumm, as well as patent cures for venereal diseases. The books barely mentioned sex itself, with the exception of passing references to “French” or “69.” Prices were not listed, either. Essentially, these pamphlets were Storyville’s marketing tools.

Arceneaux’s interest led her to write her beautiful new book, Guidebooks to Sin: The Blue Books of Storyville, New Orleans. And she’s helping to produce an exhibit that opened at the Center on April 5th titled Storyville: Madams and Music, which will look at the rise and fall of the district, as well as the jazz that grew up alongside it.

Arceneaux’s interest led her to write her beautiful new book, Guidebooks to Sin: The Blue Books of Storyville, New Orleans. And she’s helping to produce an exhibit that opened at the Center on April 5th titled Storyville: Madams and Music, which will look at the rise and fall of the district, as well as the jazz that grew up alongside it.

I’d seen the famous 1885 map of San Francisco’s Chinatown produced for the city’s Board of Supervisors detailing which buildings were brothels, gambling dens, opium dens, and so-called “joss houses,” or temples, in the course of researching my new book, Daughters of Joy. I’d also found tourist guides to Chinatown and to the adjacent Barbary Coast, San Francisco’s own Storyville. Talking with Arceneaux has inspired me to look again for West Coast versions of such “blue books.”

The highlight of the evening for me, and surely for Arceneaux, was the “ham kick” (watch the video here) – a re-creation by her colleague, Nina Bozak, of an athletic contest staged in some Storyville saloons at the turn of the 20th century. The women would take off their unmentionables and compete with each other to kick a ham strung up on a rope slung over a beam, which the proprietor could raise or lower at will. The winner – the woman who showed the most and/or managed to kick the ham the highest – got to keep this valuable foodstuff. While the re-creation was light-hearted, the fact that women competed in such a way for food is a reflection of the harsh life many of them lived.

All in fun, the authors and actors involved in the opening night event staged a “ham kick” of their own (they used a real, seven-pound bone-in smoked ham, though they did keep their knickers on.) Arceneaux hadn’t intended to compete until she was prodded back onto the stage by Bozak, who is a library cataloguer as well as a dancer and choreographer. It was Bozak who’d found a mention of the “ham kick” in Al Rose’s 1974 book, titled Storyville, New Orleans. (A more recent history of the district, Spectacular Wickedness: Sex, Race, and Memory in Storyville, New Orleans, by Emily Epstein Landau, published in 2013, doesn’t mention this frivolity.)

All in fun, the authors and actors involved in the opening night event staged a “ham kick” of their own (they used a real, seven-pound bone-in smoked ham, though they did keep their knickers on.) Arceneaux hadn’t intended to compete until she was prodded back onto the stage by Bozak, who is a library cataloguer as well as a dancer and choreographer. It was Bozak who’d found a mention of the “ham kick” in Al Rose’s 1974 book, titled Storyville, New Orleans. (A more recent history of the district, Spectacular Wickedness: Sex, Race, and Memory in Storyville, New Orleans, by Emily Epstein Landau, published in 2013, doesn’t mention this frivolity.)

And guess who won that evening’s contest?

“I won the ham kick by audience acclaim!” Arceneaux told me. She took her prize home that night (the ham came packaged in a red, mesh bag along with onions and other crawfish boil additions) and later donated it to J. & J. Sport’s Lounge because she and her husband are trying to cut salt from their diets. When I sat down with her several days later, Arceneaux was still glowing over her triumph in this bawdy contest from New Orleans’ past.