At this year’s annual gathering of the Community of Writers, I was honored to give the opening talk. Here are my remarks.

***

I’m so happy to be here… to help celebrate the rollicking and generous spirit that has infused our Community all these years.

How many first-timers are here today? Raise your hands…

Well, for you newbies, you’ll see what I mean about community spirit here during the Follies later in the week. Or you may discover it while connecting with other writers over dinner or while hiking on Thursday with your fellow work-shoppers.

I have vivid memories of how I felt my first time.

I’d been a newspaper and magazine journalist for decades….and I felt way out of my comfort zone with so all these fiction writers. The workshop leaders and notable alumnae at Squaw that year, at least on paper, seemed like an intimidating bunch. Amy Tan, Jim Houston, and Annie Lamott were all there my first week.

I remember rooming with a much younger writer from L.A. – someone who was writing fiction involving cyber-sex, as I recall. I can only guess what she thought about getting stuck with a Wall Street Journal reporter. While my roommate spent every night partying with other writers, I was a mom reading my manuscripts in the evenings, missing the five and seven-year-old boys I’d left at home.

But, for me, the most lasting gift of that first summer was finding my community. For many years, I’ve come to the valley: first as a participant in the non-fiction workshop, then as a staffer and, eventually, as a board member… I’ve discovered a group of people from different places and life circumstances who have one thing in common…

… a love of and dedication to the art of storytelling. And a belief that carefully crafted words matter. The famous writers among us and the newbies all have at least one thing in common – we’re here together struggling over the craft of how to best put words to paper.

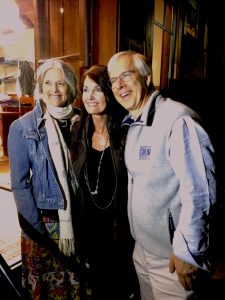

Now, some of those same people I spent a week with fifteen years ago have become some of my closest and most trusted friends. Through three books and many articles, the nonfiction author and staff member Frances Dinkelspiel has been my first reader…

…and the nonfiction writing group in San Francisco she invited me to join after we met at Squaw, North 24th Writers, has become my life raft, helping me develop my craft. This has been especially valuable to me lately. Many of us are struggling to stay afloat in a world where we’re being told, over and over, that our work as storytellers doesn’t matter.

Since our work as writers is mostly solitary, the question many of us are grappling with is how to summon up the concentration required to produce deep and honest writing, especially a time when politics is so depressing and scary. How do we keep going…?

Well, I’m going to make the case for finding and building a writing community…

The way I’ve tried to do it is by reaching out to other writers for support and encouragement – the antidote to standing by myself at my writing desk every day and living in my own head so much, usually in the nineteenth century!

I work best in the morning so you’ll find me at my desk from about eight until noon each day. When I’m deep into a project, I’ll start the day by meditating – I use one of the meditation apps – and I force myself to ignore the news and email until after I’ve gotten my writing done.

After that, I turn outward: I take walks with friends and spend a lot of time in the afternoons doing research in libraries and attending bookstore readings. I try my best to show up for the readings of friends I’ve met here and in other parts of the writing community.

That’s one of the reasons I’m so grateful for the friends I’ve made here – and for the wider literary community that is thriving in California, thanks to so many grassroots organizations like the Community of Writers and California’s great community colleges and university system.

Up and down the state, tiny workshops and reading series take place up that connect writers and readers. At libraries and gatherings like this one that offer platforms to women, to writers of color, to older people, and to LGBTQ people. That’s a quiet, but very powerful form of resistance – a way to come together and value each other by listening.

I’d like to tell you a story about how the Community of Writers offered a welcome to someone who lived on the margins of society. To me, this is a story about embracing difference and generosity of spirit – qualities I hope you’ll experience this week.

His name was Paul Radin. Old-timers might remember his dramatic entrance one summer to our annual gathering when he arrived on horseback, wearing his flat-brimmed hat and western boots.

He lived on a property his family owned on the Truckee River, close to nature and to Squaw Valley, and, although he was born in Boston to a Jewish family, he immersed himself in Native American culture, often attending pow-wows.

Paul was an outsider who found support and friendship at the Community of Writers, particularly from the novelist Louis B. Jones and the radio host and editor Andrew Tonkovich. Late in his life, a bear moved into Paul’s cabin, pushing Paul out into the woods. If he wanted to go into the cabin to get something, say a book of poetry or a cooking pot, he would blast his air-horn to scare the bear out – long enough, at least, for him to retrieve whatever he was looking for.

Paul was shy and generally mistrustful of most people, but he welcomed Louis and Andrew, particularly when they brought him gifts to ease the pain of his cancer towards the end of his life. Before he got too sick, he’d come to the Community of Writers gatherings, and sometimes reading his shamanistic poetry on the night of the follies.

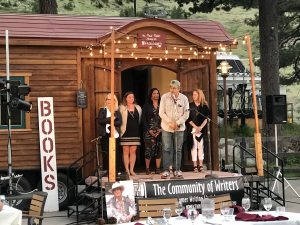

Please remember Paul’s whimsical spirit and his family’s kind donation to honor him and the Community when you look at the Dream Wagon, our tiny house on wheels. Like so much at the Community of Writers, it was born out of a spirit of generosity. It’s handmade. It’s a little quirky – made from redwood beams that were salvaged from beneath someone’s porch.

Poke your head into the “Dream Wagon” sometime this week and browse through some of the books by staffers and alumnae. When you’re there, maybe think of the spirit of our annual gatherings for nearly half a century: the way that different people travel from all over the state and the country to spend week together as a creative community. The spirit of Squaw reflects the kind of inclusiveness that welcomed Paul.

I truly hope you I have as good and life-changing an experience at Squaw this week as I have had. You are now part of a community that has played a role in nurturing some of the most significant writers and voices to come out of America…and we’ll be marking our half century beginning next year.

One of the things we’re doing to mark that half century is an oral history project, to make sure we record the memories of some of the earliest participants in the Community.

The novelist Richard Ford, who’s best known for The Sportswiter and Independence Day, for example, first attended in the early 1970s. He’d been a student of the Community’s co-founder, Oakley Hall, at U.C. Irvine and, at Squaw, he was in a workshop led by the Paris Review co-founder Peter Matthiessen, the author of The Snow Leopard.

Richard Ford then returned to Squaw as a staffer and, one year, sat out on the deck in the sun with a young Amy Tan, discussing her first short story. When Amy first arrived, she was a technical writer, working 90 hours a week, and had never been published as a creative writer. Her experience at Squaw helped give her the confidence to weave together the stories she’d been writing about mothers, daughters, and the immigrant experience.

The next time Richard Ford came across Amy’s story they’d discussed outdoors that summer, Amy had woven it into her book, The Joy Luck Club which became a bestselling novel and a movie.

That’s the spirit of the Community: writers helping other writers do their best work. Some have published books that have become bestsellers while others have only shown our stories to friends…

…but we all grapple with words and how to get them right. And that’s the focus of this week.

The history of the Community of Writers began just like that: with good friends coming together. Starting in the late sixties, the novelists Oakley Hall and Blair Fuller, who were both living in the valley at the time, decided to invite their writing pals and students up to Squaw to spend a week in the summer workshopping their writing.

Behind the scenes, there were people who quietly made these often-raucous gatherings possible. From the very beginning, Barbara Hall worked alongside her husband Oakley on the workshops, so did Diana Fuller, who was then married to Blair – checking people in, spreading out the pastel tablecloths that are still used today, and doing some of the cooking.

Diana co-founded and ran the screenwriting program for many years, and Barbara, in turn, brought her gifts as a photographer to the portraits she took of Peter Matthiessen, the poet Galway Kinnell, the screenwriter Gill Dennis, Robert Stone and many others that you’ll see hanging on the walls near the office.

This is the first year Barbara won’t be at Squaw – she died in early June. Luckily, she helped guide her youngest daughter, Brett, who is now the Community’s executive director, into that role.

Let’s take a moment to think of Barbara….

…and send our deepest condolences to her daughters Brett, Sands, and Tracy, who took such loving care of their mother in her old age.

A group of closely-knit families – the Halls, the Fullers, the Ancinas’s, the Joneses, the Klaussens, the Alvarez/Tonkovich’s, and the Millers, the Naifys, have created the environment for you to connect with other writers. This is your chance to listen carefully to how they respond to your work, and show the same care and generosity to them that they’ve shown you.

I’ll warn you now: it can be a hard week, particularly if you’ve never had your work critiqued before in a workshop.

For me, my first summer here was kind of like that Warren Zevon song that Linda Ronstadt made famous: Let me play it for you…

“Poor Poor Pitiful Me”. Remember the line about “being worked over good” by the guy from Hollywood who….

“Put me through some changes Lord

Sort of like a Waring blender”

That’s pretty much how I felt after my first workshop week: not exactly like a smoothie, but close.

I had a lot to think about when I got home based on my fellow workshopper’s comments. While some of the criticism was hard to take, it was valuable afterwards. And, like most of us, I never fully absorbed the praise the piece also got during workshop….

Then, about nine months later, I wrote a story for the Wall Street Journal that caused quite a commotion. A publisher emailed me to ask if I’d consider writing a book based upon the story.

I had no idea who that publisher was – as it turned out, he was kind of a big deal – but I DID know a literary agent – and that was Michael Carlisle, who runs the nonfiction program. He took me on as a client and negotiated a very good book contract for me.

By the time I arrived at Squaw the following year, in 2004, I had the prologue of what would become my first book, The House of Mondavi, to submit to our workshop.

And here’s the incredible thing. One of the leaders of the nonfiction workshop that year, Moira Johnston Block, agreed to become my mentor for that first book – reading every single chapter and helping me to learn how to break some of the bad habits I’d picked up as a long-time journalist – like using too many quotes. Most importantly, she taught me how to write in scene.

Again, I was part of a continuum at Squaw…. a much more accomplished writer – Moira had written seven nonfiction books at that point — took me under her wing and guided me as I wrote my first book.

Now, as a workshop leader myself, it’s my turn to help other writers tell their stories.

So, here’s my advice to you on that scary morning when your piece is being workshopped.

*Bring a notebook and pen and spend that time listening to the comments.

*Try not to say much and don’t waste your breath defending your work. Just listen.

*When your session is done, put the piece and your notes away for a week, or two, or even three before coming back to it with a fresh eye.

Just as importantly, be on the look-out during the week for people in your workshop whose comments are particularly helpful to you. They’re the people you’ll want to connect with after the week is over. They could become your first readers – and you may want to start a writing group of your own.

Unlike other writing conferences, this week at Squaw is more about the work – the words, the writing, and the stories – than about the marketing.

Yes, there are editors and agents here too: some of your work will catch their attention. But their primary goals – at least for this week – are for the feedback to take place that will help you push your work to the next level.

While some of you are new to the writing world, others of you have been doing it for a very long time. A number of the readers in this year’s published alumni readings were first at Squaw in the 1990s – proof of just long it can take for a good book to gestate. All of us – no matter where we are on the continuum – can get better.

For me, the deeper message of my experience of Squaw, and of spending the time together in this high-altitude setting — is that the work we’re doing as storytellers IS valuable.

Our words matter and our stories matter. They help us build empathy by looking through someone else’s eyes. As Dave Eggers wrote in the Times about a week ago, writing and other forms of art expands our “moral imagination and makes it impossible to accept the dehumanization of others.”

We can help each other learn how to make our stories even more effective in delivering that gut punch or eliciting the tears we’re hoping to bring to your readers’ eyes, or whatever your goal may be.

Our community is committed to the idea that reading and writing stories are portals to enter the world of someone different than ourselves. A way to open us up to the experience of the other – and to help close the yawning empathy gap which seems, increasingly, to divide us from each other.

That’s my goal with the nonfiction I write – to close the empathy gap. I focus on little-known stories from history. It was a natural evolution from the reporting I’d done for so long.

My first book was a hybrid of journalism and narrative history: in it, I told the true story of four generations of a Napa Valley wine family and their struggles over a billion-dollar family business. Part family saga and part Shakespearean tragedy, it was called The House of Mondavi: The Rise and Fall of an American Wine Dynasty.

My second book was titled Lost Kingdom: Hawaii’s Last Queen, The Sugar Kings, and America’s First Imperial Adventure. It was about Hawaii’s last monarch and her overthrow – a profoundly sad story that also explores family dynamics and lost fortunes set in the late nineteenth century.

For the last several years, I’ve again returned to the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The book I’m working on, The White Devil’s Daughters, centers around a mission home in San Francisco’s Chinatown where thousands of Chinese girls and women found refuge from sex slavery and other forms of servitude.

As the girls and women we see in the news today, they were caged and separated from their families.

I based the narrative on tens of thousands of pages of documents from the National Archives and elsewhere. It’s also a work of investigative history, in the sense that I’m aiming to tell the stories of people who, for the most part, left only the faintest trace in the historical record.

The story starts in the 1870s, when the rabble-rouser Denis Kearney were shouting “The Chinese Must Go” and a California gubernatorial candidate, James Phelan, ran on the slogan “Keep California White!”

That racism against the Chinese took hold across the state and legislators, in 1882, passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which remained a law until it was repealed in the 1940s.

During that period of brutal racism, there was a small group of people who became allies to the Chinese sex slaves. I wanted to learn how and why those people who became their allies could bridge that empathy gap – to take the risks to protest on behalf of people whom many their fellow white-citizens didn’t even consider fully human. They were pioneers in the movement to fight sex slavery and human trafficking of Chinese women and girls.

And, in turn, how did these girls and women – facing the most extreme forms of brutality and confinement – gain their freedom?

The story is a dark corner of American history, but one that I think has resonance today. It’s coming out next May. My editor at Knopf, Ann Close, is a longtime Squaw faculty member. Likewise, my literary agent for all three of my books has been Michael Carlisle.

So, I guess I’m up here today because my story of connecting with other people at Squaw is an unusually fortunate one. I was lucky to find Michael, and my editor Ann, who was also Jim Houston and Oakley Hall’s editor: I feel proud to be part of that continuum.

Connecting with other writers and joining the continuum is a big benefit of being part of the Community of Writers.

But I don’t think nabbing an agent or an editor should be your main goal this week. I’d urge you, instead, to focus on the work and on building friendships with other writers. Our community is a special one because we emphasize the work – and on collaboration to make it better – rather than on the business side of publishing.

On a day-to-day basis, it was my greatest stroke of good fortune to have made friends with some of the people in that first workshop, who then went on to support me as I made the transition from journalist to author…

They’re the ones – the eight women in my workshop North 24th – who’ve seen me at my worst and my best over the years. They’re the ones, in the words of Annie Lamott, who’ve read all of my shitty first drafts…

…our workshop has been together for more than twenty years. I’m a relative newcomer to it having joined fifteen years ago. I count my blessings every day to have been invited to join them by my fellow workshopper Frances all those years ago. In fact, they workshopped this talk before I dared make it.

So, for those of you who are new to the Community, here are my last words of

advice:

Read closely.

Try to read each piece twice, if you can – the first time without marking it up.

Be generous.

Get enough sleep.

Make friends with your favorite readers after workshop week ends….

And…remember… that one drink will hit you like two or three at high altitude!