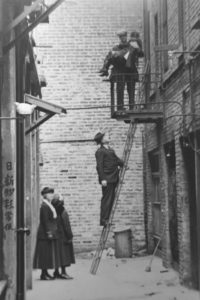

The best-known image of the pioneering anti-trafficking crusader Donaldina Cameron at work was taken in the early 20th century in a garbage-strewn alley in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

Donaldina Cameron (left, standing) with interpreter and police officers staging a rescue of a Chinese girl. Courtesy of Cameron House.

Cameron, wearing a full black skirt that fell just above her ankles and a dowdy, small- brimmed hat, gazes toward the camera. A man in a suit stands partway up a ladder propped against a brick building. On a balcony above him, a man who appears to be a plainclothes police officer holds a girl in his arms. She has a long black braid hanging down her back and is the “slave girl” supposedly being rescued.

We don’t know who the photographer was or why the photograph was taken.

We do know that staging of photographs was the norm for most turn-of-the–century photography and the image was probably taken to accompany one of the many newspaper articles about Cameron’s rescue work at that time.

But this photograph has become a visual embodiment of what some scholars call “the white rescue myth.”

Cameron, and the women who came before her who founded the Presbyterian Mission House, were white. They described what they did as “rescue work.” Their goal was to protect, educate, and convert vulnerable girls and women. And most of those girls and women were Chinese (although Japanese, Syrian, and other nationalities of women also took refuge at the home.)

In the years I spent researching and writing about the individual lives of women who lived and worked at the rescue home at 920 Sacramento Street, I learned that many, if not most, of them were not “rescued” by policemen on ladders or missionaries breaking into brothels, especially in the later years of the home.

Many, if not most, arrived there through their own volition. They sought out the home, often with the assistance of friends, and had to agree to stay there for at least six months. In later years, many were paid boarders who would stay there while their husbands or fathers were away, or while waiting to clear immigration into the U.S. as an alternative to the bleak detention facilities at Angel Island, which opened in 1910.

The White Devil’s Daughters documents a remarkable, collective story of women helping other women and reaching across divides of race and class to do so. Cameron and the other white mission workers not only relied mightily on the Chinese residents-turned-aides in the home: they simply could not have done their jobs without them.

The most important stories I found were those of the girls and women who escaped sex slavery to find their freedom. I also discovered that some of the home’s Asian residents chose to continue the fight against slavery by working as translators in court and among immigration officials and in running the home on a day-to-day basis. They, too, decided to take part in the ongoing fight against slavery.

What’s generally overlooked in this photograph of Cameron at work is that she’s standing next to another woman – possibly the interpreter Ida Lee, one of the many Chinese women who worked closely alongside her over the years. Look closely: this iconic photograph of “rescue work” tells a very different story than one might expect.

The second photo of this rescue scene with Donaldina Cameron (center) and Chinese interpreter to the right. Courtesy of Cameron House.