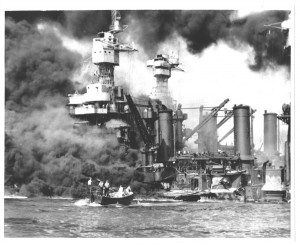

In the early hours of Sunday, December 7, 1941, seventy years ago, Japanese bombers launched a surprise attack against the US military base at Pearl Harbor. The devastating attack on Hawaii, which was then an American territory, profoundly shook the nation and hastened its entry into World War II.

But nearly seven decades before “Remember Pearl Harbor” became a national rallying cry, the same waters were a battleground over Hawaiian sovereignty. In the 19th century, Hawaii was an independent nation — a constitutional monarchy modeled on Great Britain’s — as well as a reluctant bride in a contest among the era’s reigning and rising superpowers. In it, they saw the potential for a deep water port that would make Hawaii an ideal stopover for large ships traveling between North America and Asia.

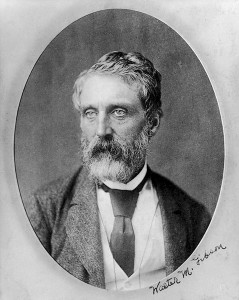

Native Hawaiians rightly feared that they would lose their nation if they ceded rights to the Pearl River area, which they called Pu‘uloa. They found an unlikely champion in a tall, blue-eyed American adventurer named Walter Murray Gibson. A Southerner with a murky past, he had arrived in the islands in 1861 as a Mormon missionary. With a genius for spotting opportunity, he took up the quixotic cause of saving the Pearl River basin.

He entered the seething and unstable political scene of the island nation’s capital of Honolulu in 1872, the year of King Kamehameha V’s death. Fluent in Hawaiian, he had renounced his U.S. citizenship to become a citizen of the Hawaiian Kingdom. When impassioned debates over the fate of the Pearl River basin, an area which was about a day-long carriage ride to the northwest from Honolulu, became front page news, Gibson started using the pages of his own Hawaiian-language newspaper to espouse the populist message of “Hawaii for Hawaiians.”

The basin had deep cultural resonance for Hawaiians, whose ancient ancestors believed that the shark goddess Ka‘ahupahau guarded the Pearl River’s treacherous entrance, a narrow channel through coral reefs where saltwater mingled with fresh. It was the wealth of oyster beds that gave the area its English name and native Hawaiians had long dived for these prizes in the harbor’s waters.

But the Pearl River basin lured a succession of British and American naval officers carrying magnetic compasses and surveyor’s chains, and in 1873 a military commission under secret instructions from the US secretary of war William W. Belknap examined various ports in the Hawaiian Islands for possible defensive and commercial purposes. That same year, King William Lunalilo became the first Hawaiian monarch to give serious consideration to a proposal from the US offering the harbor in exchange for allowing Hawaiian sugar (which planters began cultivating in the 1870s) to enter the American market duty-free. Trade and defense were becoming inextricably bound, and in neither case were native Hawaiians reaping the potential benefits: The vast majority of the Hawaiian planters who stood to benefit from the agreement were, in fact, white foreigners.

In his public statements, David Kalākaua, who ascended to the throne in early 1874, had long been opposed to ceding rights to the Pearl River basin. Likewise, Gibson argued against giving the estuary to the United States, and in November of 1873, he printed a traditional Hawaiian chant, or *mele*, expressing Hawaiian opposition to the deal, which would give the U.S. exclusive access to the estuary in exchange for trade benefits. It ended with the warning:

Be not deceived by the merchants,

They are not only enticing you,

Making fair their faces, they are evil within;

Truly desiring annexation,

For several more years the basin remained in Hawaiian possession. But Gibson and King Kalākaua could only hold off the diplomats, politicians, and powerful sugar planters for so long. In 1887, in the midst of an economic depression and intense pressure from the nation’s businessmen, a Reciprocity Treaty was signed which gave the United States exclusive rights to the area in exchange for trade benefits for exporters of Hawaiian goods to the states. The editorial writers of the kingdom’s Hawaiian language newspapers reacted with dismay, particularly Joseph Nāwahī, a respected native journalist and legislator. He had predicted in 1876 that reciprocity “would be the first step of annexation later on, and the Kingdom, its flag, its independence, and its people will be naught.”

The king’s sister, Lili‘uokalani, was likewise distressed by the deal with the Americans. On Monday, September 26, 1887, she wrote in her diary, “King signed a lease of Pearl river to U. States for eight years to get R. Treaty.” Seeing the lease as an unequal swap for a treaty that benefited the island kingdom’s sugar planters, she concluded darkly, “It should not have been done.”

Gibson, meanwhile, fled the country amidst corruption charges aboard a San Francisco bound steamer owned by the kingdom’s leading sugar planter, Claus Spreckels. He had barely escaped hanging by an angry mob. Ailing and exhausted, he sought to commit his version of events to paper, since he felt the “reformers” who had chased him out of Honolulu had ignored his years of faithful service to the Hawaiian people and his brave, but increasingly unpopular, defense of their interests. He died a few months later in San Francisco. According to the newspapers who reported his death, his last word was “Hawai‘i.”

Gibson’s embalmed body returned to the islands covered with a Hawaiian flag. Once it arrived, streams of visitors came to view the body, including some of Gibson’s fiercest critics: Judge Sanford B. Dole, his brother George Dole, and Lorrin Thurston, who would later lead the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The three men joined the crowd moving past his coffin. Thurston was shocked to see that the embalming fluid had turned Gibson’s skin very dark, eerily contrasting with his long white beard and silver locks. They left the reception room and stepped out onto the street.

“What do you think of it?,” Dole asked his brother and Thurston. After a few seconds’ pause, George answered, “Well, I think his complexion is approximating the color of his soul.”

Today, Gibson is nearly forgotten. Pearl Harbor, as it exists today, was created following massive dredging of the basins coral reefs in the 20th century. The US naval base at Pearl Harbor is headquarters to the commander of the Pacific Fleet, the world’s largest, responsible for patrolling a hundred million square miles of ocean.

Julia Flynn Siler is the author “Lost Kingdom: Hawai‘i’s Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America’s First Imperial Adventure,” published by Atlantic Monthly Press. For more information, please visit www.juliaflynnsiler.com.