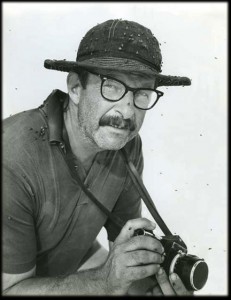

The story begins in November of 1957. The chief photographer for the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Warren Roll, climbed into the passenger seat of a small plane in Kauai. The pilot took off, heading towards a 73-square-mile privately-owned Hawaiian island of Niihau.

The plane landed roughly, smashing its landing gear and splintering its propeller. Roll, carrying his camera gear, left the pilot and set off across the island in search of the island’s one village. The Robinson family, who by that time had owned the island for nearly a century, had restricted access to it for decades. Roll, an unusually enterprising photojournalist, had successfully penetrated what was by then known as the “Forbidden Island.”

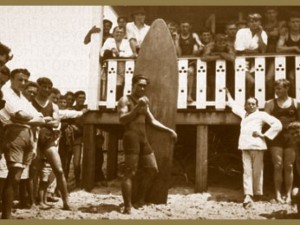

Hot, thirsty, and exhausted after walking for hours, Roll finally reached the village. He called out to the first people he saw, “Hello! Will you help me?” And they did. In a pattern that began with the arrival of Captain James Cook, the British explorer who was the first westerner to reach this archipelago of volcanic islands long-isolated in the north Pacific in 1778, the Native Hawaiians of Niihau (pronounced Nee-ee-how) warmly welcomed Roll, who, like Cook, was a “haole” or foreigner to them.

Roll then took a series of photographs for his newspaper of the Native Hawaiians who lived on the island which were published in a two-page spread in the Star-Bulletin on November 16, 1957. Its headline was “Free Though Feudal. They’re Happy on Niihau: Iron Curtain Lifted For the First Time. Much of What You Hear About the Island Isn’t So.” His scoop caused a sensation.

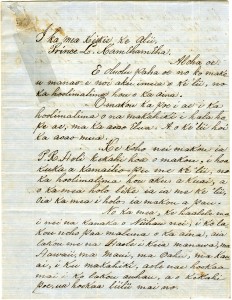

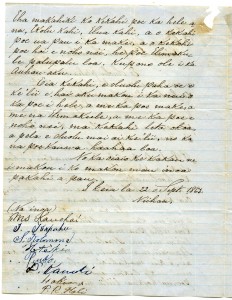

But what Roll didn’t reveal in the story how he also ended up with a crumbling, hand-written petition on bluish lined parchment paper with 105 signatures on it that remained buried in his files for years. Whether he was given the petition during that first trip, or somehow acquired it on another occasion, is not clear. But the recent discovery of this 1863 document underscores the sometimes surprising ties between the Hawaiian islands and San Francisco.

Warren Roll eventually retired from the Star-Bulletin and returned to the mainland. He died in 2008. The bulk of his archives, which included negatives from his decades of work on the islands as well as materials he collected for a possible book on Niihau, ended up in a small, wooden toy box with one of his sons, the fine arts painter Jonah Rolls. Jonah lives with his wife and two daughters in Project Artaud, an arts colony on the industrial edge of San Francisco’s Mission District.

Jonah, who was born in the islands and raised aboard a 38-foot ketch named the Flying Walrus in Honolulu’s Ala Wai boat harbor, had begun having bad dreams about his father’s archives and worried that something would happen to them. “I love having it here, but it’s slowly taking its toll,” the painter said, noting the mana or power of the island of Niihau and the burden he felt keeping his father’s archives safe.

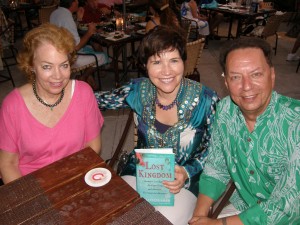

I first met Jonah after a longtime staff cameraman at KQED, Harry Betancourt, approached me in the green room after I’d been on Michael Krasny’s Forum show to talk about my book on Hawaii, Lost Kingdom. Harry suggested I reach out to Jonah, who had inherited some interesting materials on the islands from his father. I visited Jonah and his family and their home in Project Artaud twice, and Jonah ended up asking me to get in touch with the head of the Hawaii State Archives to translate the document from the Hawaiian into English and also to put it into its historical context. Within a day, Jonah had the translation.

Jonah had long suspected the document had something to do with the purchase of the island. Indeed, in early 1864, the Robinson family had bought the island for $10,000 in gold from Hawaii’s King, who had found it somewhat troublesome to own and thus wanted to sell. Located 17 miles off the coast of Kauai, Niihau suffered from regular droughts. What’s more, the king had some difficulties collecting rents from the Hawaiian tenants. The Robinsons, which had come to the islands from Scotland after a long stopover in New Zealand, moved to Niihau with the plan of raising cattle and sheep.

Early in the 20th century, when Hawaii was still an American territory and the archipelago had not yet become the 50th state, the Robinsons decided to restrict access to the island only to those already living there – mainly a few hundred Native Hawaiians. Outsiders could only visit with the family’s permission.

As the decades passed and the Hawaiian language was actively suppressed by the territorial government, Niihau became the only place in the world where Hawaiian was the predominant language spoken. Legends and myths sprung up about the island, which is the geologically oldest of the seven inhabited Hawaiian Islands, and also said to be the birthplace of the volcano Goddess, Pele.

Roll, who had served in as an aerial photographer for the Navy during WWII and the Korean War had the knack for being in the right place at the right time and he wanted to see the place for himself. His son Jonah believes he intended to land there in search of a journalistic coup. (Click here to see some of Warren’s photographs.)

Long after that crash and trek in 1957, the memory of what Warren Roll saw on Niihau stayed with him. “He became completely obsessed,” his son Jonah recalls. He began collecting documents, newspaper clippings, and other materials – some of which ended up in what he called his “Unauthorized Niihau Scrap Book.” Upon retiring from the paper, he shipped a file cabinet with him to the mainland. It included background on the Robinson family and, according to Jonah, at one point had contact with an estranged member of the Robinson family about what he’d found. The crown jewel of his collection was the document in Hawaiian from 1863.

Click here for a translation of the 1863 Niihau Petition

After getting the translation done by a staffer at the Hawaii State Archives, Jonah became even more concerned about the burden of taking care of it. It turned out to be a petition from virtually every single resident of the island at the time asking the King for a new lease of the island to the island. The petition came at the time that the Robinsons were negotiating to buy it from the king. Although there are similar letters between the island’s residents and the Minister of the Interior, the archive did not have this one — and there is no mention in the standard histories of nineteenth century Hawaii of an attempt by the native Hawaiian residents to maintain their grip on the island (with the exception of a fragment of this letter in an appendix to a book about Ni’ihau published in 1989.)

The ending to the story? Jonah Roll has offered to donate the petition to the Hawaii State Archives, sending it back to the islands along with his father’s photo archive. As for the mystery of how this document ended up in an artist’s studio in San Francisco, it’ll probably never be solved. “I can only wonder where the letter came from,” he says. “But I want to get it back to Hawaii, where it belongs.”