‘The Divine Miss Marble’ Review: Serving With a Smile

By Julia Flynn Siler

In 1973, Billie Jean King faced Bobby Riggs in a tennis match dubbed the “Battle of the Sexes.” My 13-year-old self, along with 90 million or so other people, sat transfixed in front of the television as Ms. King walloped her much older, provocatively sexist opponent. She became a tennis hero for my generation and her victory became a triumph for women, including rank amateurs like me.

As a superstar female athlete, Ms. King paved the way for many others, including Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova. But before Ms. King there was Alice Marble, a trailblazer in women’s tennis during the 1930s. In Robert Weintraub’s entertaining but uneven biography, “The Divine Miss Marble: A Life of Tennis, Fame, and Mystery,” we’re introduced to a hardscrabble teen who eventually becomes the pre-World War II era’s biggest female tennis star.

The line from Alice Marble to Billie Jean King is direct. Both women were municipal players from California—perfecting their strokes on city courts rather than country clubs. Marble was from San Francisco; the young Billie Jean was from Long Beach, where her father was a firefighter. By the early 1960s Marble, a legendary Wimbledon winner who changed women’s tennis forever with her ferocious serve-and-volley style, was teaching the game. One of her young students was Billie Jean: Marble helped improve her serve, which would later prove lethal against Riggs. “For the first time in my life,” Ms. King would later say, “I sensed some kind of legacy that I was part of.”

Alice was the fourth of five children, born in 1913 to a rancher and his nurse wife in the Sierra Nevada. The family moved to San Francisco in 1919, during the flu pandemic. Alice’s father soon died, leaving her mother to raise the large brood. Influenced by her older brothers, Alice became a tomboy—as a teen she shagged fly balls during batting practice for the San Francisco Seals, a minor-league team.

Soon she discovered the Golden Gate Park municipal courts, often sopping wet after heavy morning dew—forcing players to drag blankets across them in those presqueegee days. Alice began playing in local tournaments and soon rose to state-wide competitions. As a 15-year-old, she was raped leaving the park one evening—an incident only revealed in “Courting Danger,” Marble’s posthumous memoir. “It made me tough,” she wrote, “and made me turn all the more to tennis to counteract my low self-esteem.”

Soon, Marble met a woman who would influence her more than anyone else: Eleanor “Teach” Tennant, her “coach/teacher/manager/Svengali and likely, for at least a brief time,” writes Mr. Weintraub, “lover.” Tennant, who also grew up in San Francisco, took over the younger woman’s life and finances for more than a decade, as they lived and traveled together.

Marble mingled with Tennant’s other students and friends, including such Hollywood stars as Marlene Dietrich, Clark Gable, Carole Lombard and Marion Davies, the longtime paramour of William Randolph Hearst. Meanwhile, Marble’s prowess on the court—despite being diagnosed with tuberculosis in her early 20s after collapsing midmatch at Roland-Garros—earned her 18 victories at the U.S. Nationals and what would now be called Grand Slam events.

The book’s play-by-play recounting of tennis matches, drawn mainly from the accounts of contemporary sports writers and Marble’s two memoirs, are fast-paced and fun. But the real treat is the book’s spin through the glamorous worlds of Hollywood, Palm Springs, San Simeon and Wimbledon that our working-class heroine navigates on her way to stardom. The sport of tennis, then as now, can serve as a springboard into elite social circles. Marble’s athletic gifts, coupled with her glamour, fluid sexuality and early embrace of shorts at a time when most women players were still wearing longer dresses, made her a media darling.

Perhaps the most intriguing part of Marble’s story is her claim that she served as a spy during World War II, traveling to Europe on behalf of the Office of Strategic Services (the predecessor to the CIA). In “Courting Danger,” she claimed that her mission was to expose a former lover, supposedly a Swiss banker, believed to have been laundering funds for the Nazis. Marble is forced off a road in the Swiss Alps, the evidence she gathered of Nazi war crimes snatched away from her. As she turns to run for her life, she’s shot in the back.

Mr. Weintraub doesn’t prove or disprove this claim; frustratingly, this compelling episode of Marble’s life remains a mystery. Yet the author nevertheless begins his book with her supposed car chase through the Swiss Alps. Does it matter if the story is true? Yes, because of the teasing prominence Mr. Weintraub gives it in his book’s preface.

Just as fascinating were Marble’s many creative side hustles to support herself after many years of being underpaid as a female tennis star. She helped research and write scripts for a new comic, “Wonder Woman”; wrote a column for a tennis magazine in which she anticipated the civil-rights era by advocating, in 1950, for the black player Althea Gibson (“it’s also time we acted a little more like gentlepeople,” she wrote, “and less like sanctimonious hypocrites”); sang torch songs at the Waldorf Astoria in what she called her “froggy contralto”; and taught tennis to Sally Ride, the first American woman in space.

Mr. Weintraub unabashedly describes himself as “merely the latest in a long line of Alice Marble admirers.” He sensitively documents her struggles and shows how her achievements on the court did not lead to riches. She lived in strained circumstances for decades, even with many years of financial support from Will du Pont, a former lover. If you’ve ever wondered what the world of competitive women’s tennis was like before King, Evert and Navratilova, “The Divine Miss Marble” hits that sweet spot.

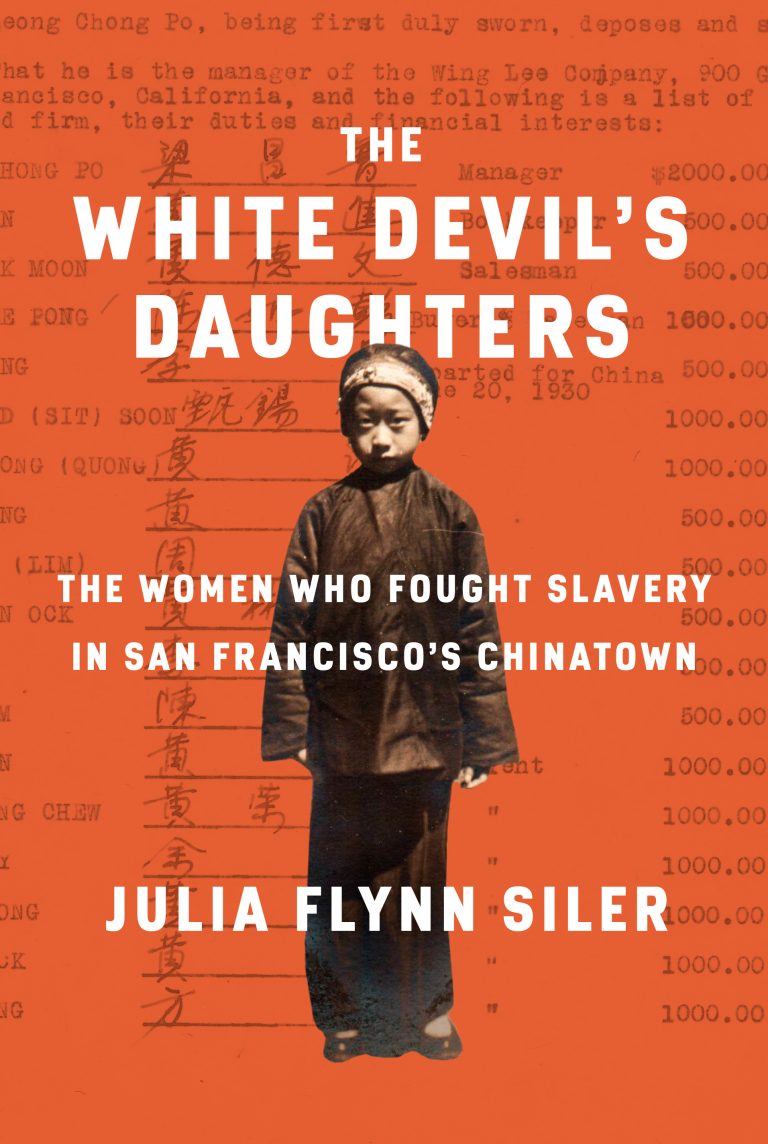

Ms. Siler is the author of “The White Devil’s Daughters: The Women Who Fought Slavery in San Francisco’s Chinatown” and is a former staff writer for The Wall Street Journal.

To read the article on the WSJ.com site, please visit here.