Trespassers at the Golden Gate

BOOKSHELF – The Wall Street Journal, published March 6, 2025. ‘Trespassers at the Golden Gate’ Review: A Death in the Bay”

By Julia Flynn Siler

Around dusk one evening in November 1870, a steam-powered ferry pulled away from Oakland’s wharf, heading to San Francisco. Aboard was the prominent California attorney and politician A.P. Crittenden, along with his wife, Clara, and their 15-year-old daughter, Carrie. Mother and daughter had just disembarked from a long journey on the transcontinental railroad and Crittenden had come to meet them.

Sitting together on the open-air deck, the Crittendens were approached by a veiled woman in black. Suddenly Clara saw a blaze of light and heard a pistol-crack from a shot “so close that it singed her dress.” Her husband, who took a bullet to his chest, fell against Clara before toppling onto the deck.

A.P. Crittenden didn’t survive the shooting. The woman was quickly revealed to be Crittenden’s lover, Laura Fair, the subject of Gary Krist’s “Trespassers at the Golden Gate.” Mr. Krist—whose city-based narrative histories include “Empire of Sin,” which explores New Orleans, and “City of Scoundrels,” about early-20th-century Chicago—uses a love triangle gone wrong to tell a wider story about 19th-century San Francisco. He captures the city’s lawless and chaotic early years as well as the strained efforts of “community elites,” through the murder trials of Laura Fair, to achieve some semblance of respectability for the city.

After a seven-year affair, Fair had been counting on Crittenden to leave his wife, marry her and help support her daughter. And so she was shocked and dismayed to learn that Crittenden’s wife and daughter were returning to San Francisco after six months living in Virginia, threatening Fair’s hold on Crittenden. Fair was furious.Despite Crittenden’s promises that Fair was “the only wife he had on earth” and that he would “kiss no other,” Fair decided to see for herself whether he was lying. She followed him to the ferry. The scene of domestic harmony she saw infuriated her—so she shot him.

There was no question whether Fair murdered Crittenden. “I did it and I don’t deny it,” she confessed when confronted by the ferry captain. “He ruined both myself and my daughter.” The ensuing trial was intended to determine Fair’s sentence: death by hanging, or acquittal for reasons of extreme mental anguish and insanity. Ultimately Fair, a former actress who had found success as a businesswoman and investor, underwent two trials. In the first, she was cast as a “bold, bad woman” and sentenced to death.

After that sentence was overturned on appeal, a second trial painted Fair as a vulnerable single woman who’d been seduced by a scoundrel. The trials shed light on the era’s shifting attitudes toward women. A suffragist group supported Fair “from the start,” while moral reformers, hoping to clean up the city’s tawdry reputation, sought firm justice for a confessed murderer and pushed for Fair’s hanging. The jury in the second trial was more sympathetic, and Fair was acquitted.

The long dalliance between Crittenden and Mrs. Fair, as she referred to herself, resembles, at times, a French bedroom farce. Crittenden had strung his mistress along with promises that he would divorce his wife and marry her. In fact, his lies and head-spinning changes of accommodations in rented rooms, apartments and rooming houses—all aimed at keeping his mistress and wife apart in a relatively small city—make for tragicomic moments.

They also remind us how little power women possessed at that time, decades before they would win the right to vote. One of most laughable scenes took place in 1864, when Crittenden installed his lover in a room directly above his wife’s at San Francisco’s Occidental Hotel, then arranged a very public meal in which they, along with the Crittendens’ daughter, would dine together to dispel any ugly rumors of infidelity.

In addition to court transcripts and newspaper accounts, Mr. Krist has mined a rich vein of material in the Crittenden family papers at the University of Michigan. Much of the author’s account is made up of his sketches of San Francisco in the 1860s and ’70s—a time when the city’s literary scene blossomed, especially with the founding of the Overland Monthly, which published such writers as Ina Coolbrith, Bret Harte and Mark Twain. Mr. Krist uses these authors’ descriptions of San Francisco to widen his lens beyond the story of Crittenden’s murder and Fair’s trials. He describes, for instance, how Twain had become “a habitué of the dives” of San Francisco’s Barbary Coast neighborhood, “and apparently partook willingly of the hashish that was just then becoming a vogue among literary types about town.

“Trespassers at the Golden Gate” also folds in portraits of vibrant and less-famous characters roaming San Francisco during the city’s explosive periods of growth, bust and reinvention: from Ah Toy, the notorious (and litigious) prostitute, to Jeanne Bonnet, who caught frogs for local restaurants and was arrested “no fewer than 20 times for cross-dressing.” Yet the murder trial and the glimpses into the individual lives of the Crittendens and Laura Fair remain the most absorbing aspects of the book.

Mr. Krist helps us understand San Francisco’s evolution—a city described by one of its early residents as “an odd place . . . not created in the ordinary way, but hatched like chickens by artificial heat.” It was a world—far removed from the tight social controls of Mrs. Astor and Gilded Age New York—where a louche character like A.P. Crittenden could keep his wife and mistress in the same hotel and hardly anyone blinked an eye.

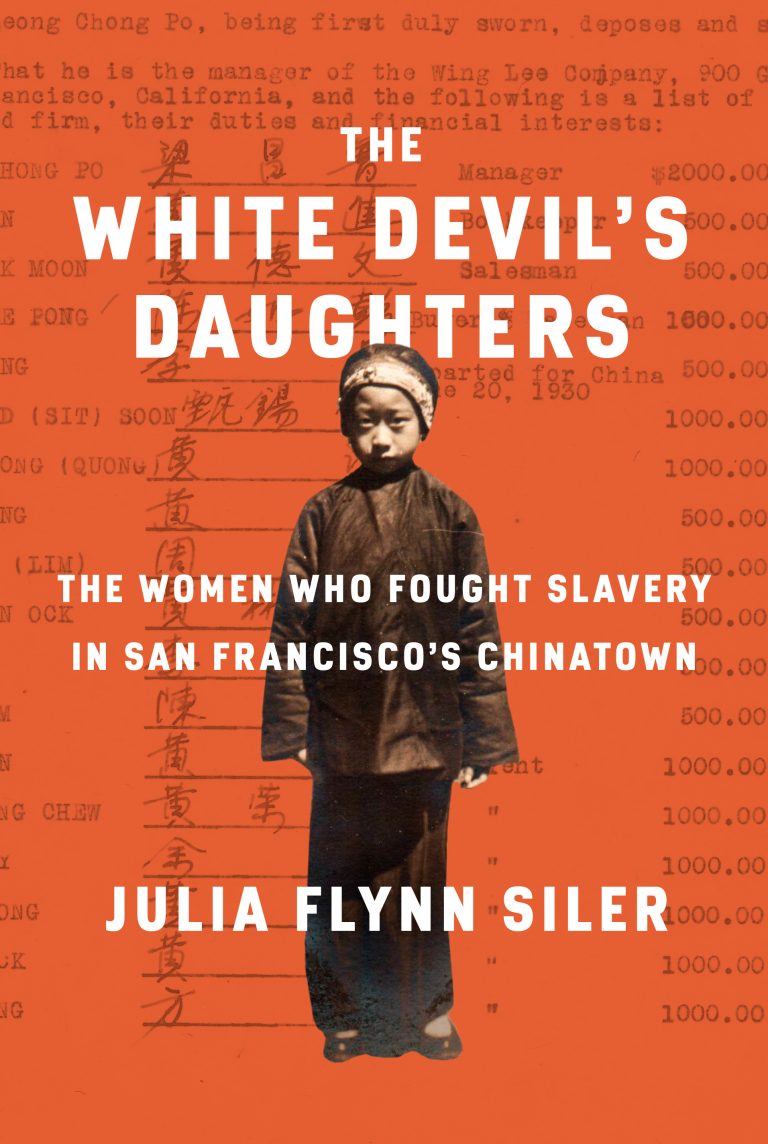

— Ms. Siler, an academic visitor at Oxford University and a former staff reporter for the Journal, is the author of “The White Devil’s Daughters: The Women Who Fought Slavery in San Francisco’s Chinatown.”