On the gusty, rain-soaked evening of January 14, 1905, Jane Lathrop Stanford prepared for bed in her mansion on San Francisco’s Nob Hill. The 76-year-old widow of the railroad baron Leland Stanford lived alone in the dark, 50-room Italianate palace, tended by servants. Suffering from a bad cold, Jane drank from a bottle of Poland Spring water before retiring and found it strangely bitter. Knowing she’d made some enemies and fearing for her life, she stuck a finger down her throat and forced herself to throw up. She then called her private secretary, Bertha Berner, and her maid, who insisted she drink four or five glasses of warm water to induce further vomiting.

The spring water had been spiked with rat poison. “I am startled and even horrified that any human beings feel that they have been injured to such an extent as to desire to revenge themselves,” Jane wrote to a friend soon after. But as one of California’s richest women and the primary benefactor of Stanford University, she had recently threatened the livelihood and reputation of a formidable man. The poisoning attempt forced her to confront the fact that someone wanted her dead.

Fleeing California for her safety, she boarded a steamship for Hawaii. She stayed at the Moana Hotel—the first grand resort to be built in Waikiki, then a quiet wetlands area with coconut groves, taro fields, and fishponds once reserved for Hawaiian royalty. She filled her days with outings and her evenings with sunsets and soothing Hawaiian music.

On February 28, 1905, after a light meal and a walk on the pier, Jane retired to her bedroom. Berner, who was staying in a room across the hall with the maid, had laid out a teaspoon of bicarbonate of soda. Jane added the white powder to a glass of water that she drank before bed to aid her digestion. Two hours later, at around 11:15 p.m., she called out for help. When Berner and the maid rushed to their employer’s room, they witnessed a terrifying sight. Jane was clinging to the doorframe, barely able to stand. Within minutes, her body writhed in contortions. Her fists clenched, her jaw tightened, and her legs splayed open. Jane knew that she had been poisoned—for a second time.

“This is a horrible death to die!” she cried.

Shortly before midnight, one of the United States’ leading philanthropists was dead.

More than a century later, the case of Jane Stanford’s murder remains unsolved. Researchers are digging—at times, literally—into the mystery as they try to understand more clearly the circumstances of her final weeks and months. Their discoveries are reshaping our understanding of the dramatic life and death of Stanford University’s founding matriarch and revealing long-hidden truths about the first leaders of California’s most prestigious university. One of the West’s most puzzling whodunits may soon be solved.

Before fleeing to Hawaii, Jane had looked forward to spending the spring at a place she called her Palo Alto Farm. She had enjoyed some of the happiest moments of her life at her country estate on the San Francisco Peninsula, surrounded by 8,180 acres in a rolling landscape of coast live oaks, manzanita, and chaparral. Stanford University today is still called the Farm—though much of its rural character long ago vanished beneath manicured lawns, medical complexes, and parking lots. What remains is a deftly cultivated origin story: a university born in 1885 of a generous act by grieving parents, the hiring of a first president who brought their vision to life, the orderly transition of a young educational facility into a world-class institution.

What’s missing from this story is the wretched and agonizing death of the school’s founding mother—and a full accounting of Jane’s role in its chaotic early years. Two decades before her poisoning at the Moana Hotel, Jane Stanford and her husband started what would become one of the world’s great universities. After Leland Stanford’s death in 1893, Jane inherited an estate that appeared, at first glance, to be massive—worth upward of $20 million, or more than half a billion in today’s dollars—but was, in fact, debt-laden and not as large as it seemed. As a widow, she financed and oversaw the struggling institution, guiding construction and managing an all-male board of trustees. As the university’s second president declared, Jane Stanford was the school’s “real founder and greatest benefactor.”

Yet for nearly a century, Jane’s murder was ignored or denied. The official version of her death was that she succumbed to heart disease in Hawaii. Even now, the university’s web page about its history does not mention Jane’s death or its cover-up. That is changing. The circumstances of her horrifying poisoning have drawn the scrutiny of true-crime bloggers and theorists, and knowledge of her role in developing the university is slowly coming to light. Jane’s erasure from much of the school’s early history raises the question of what it means to bury a piece of someone’s biography, whether in a family or as an institution. But forensic scholarship is starting to change the way we remember Jane Stanford. It may lead to a retelling of Stanford University’s founding myth—one that unseats a man and centers the story around a woman, righting a lingering wrong.

Jane’s murder occurred just as the Gilded Age was giving way to the reforms of the Progressive Era. The voraciously acquisitive lives of the Stanfords themselves, with their manic shopping trips to Europe to scoop up artworks to decorate their homes in California, seem to epitomize many of the excesses of their time. It would be easy enough to reduce Jane Stanford to simply a pampered and demanding woman who lacked a formal education, indulged in decades-long grieving, and relied on spiritualists for guidance. But Jane was far more complex than those facts suggest.

Born in 1828 to a shopkeeper and his wife in Albany, New York, Jane married young local lawyer Leland Stanford when she had just turned 22 and he was 26. He sought his fortune by moving west and eventually became one of the Big Four railroad barons of the Central Pacific line. While Chinese workers labored under brutal conditions, Leland amassed vast amounts of land and served as a one-term governor of California. He went on to take office as a Republican U.S. senator of the state from 1885 until his death in 1893. Eighteen years into their marriage, at 39, Jane gave birth to the couple’s first and only child, Leland Stanford Jr. Jane and Leland doted on their precocious son and indulged him with such delights as his own miniature train, which ran on 400 feet of track from their house to the stables at the Farm. Tragically, Leland Jr. died of typhoid at age 15 in 1884, while the family was on a grand tour of Europe. To honor him, his parents founded Leland Stanford Junior University the following year on the Farm.

Leland and Jane established the university together, a joint effort by husband and wife that was unusual for the time. They poured much of their fortune into creating the coeducational institution. Most Ivy League schools still barred women, though a number of public universities and historically Black colleges had been coed for decades. Focusing on a practical education, their school would be tuition-free.

They both saw the importance of including women as students at Stanford, though mainly to prepare them for their eventual roles as wives and mothers—a principle they incorporated into the university’s articles of endowment. “We have provided…that the education of the sexes shall be equal—deeming it of special importance that those who are to be mothers of the future generation shall be fitted to mold and direct the infantile mind at its most critical period,” Leland said. Their view that women belonged in the “domestic sphere” and men should dominate the “public sphere” was widely held at the time. But enrollment by women rose so fast that Jane in 1899 insisted on capping their number at no more than 500 at a time.

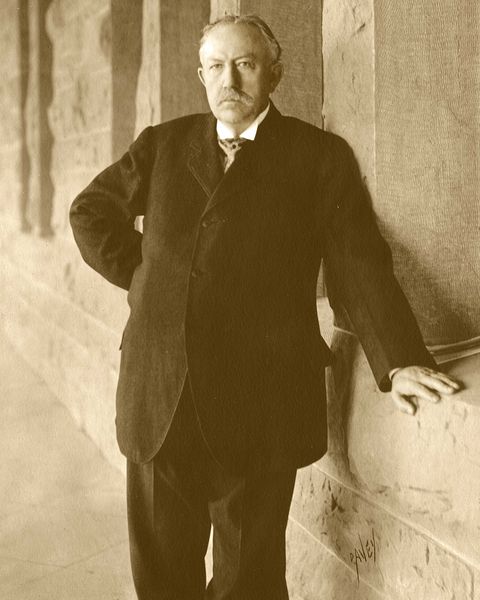

The couple hired David Starr Jordan, an ichthyologist (a scientist who studies fish) from Indiana University, as the new school’s first president. Standing six foot two, with swashbuckling confidence and a walrus mustache, Jordan had just turned 40 when he moved to California to be sworn in as president in 1891. He hired many of his former students and friends in the sciences and spent part of the Stanfords’ fortune on a new marine-research facility in nearby Monterey.

Since Leland became a U.S. senator the same year as the university’s founding, Jane took a key role in its planning. As former Harvard president Charles W. Eliot wrote in a 1919 letter to Jordan, his impression was that Jane “had done much more thinking on the subject than [her husband].” In Jane’s private journal, she wrote that it gave her “something to live for.”

The university’s first crisis struck in 1893, after Leland Sr. died. He left almost his entire estate to his widow. In an extraordinary decision for a Victorian-era woman, Jane did not close the fledgling school—as some of her advisers suggested—but, rather, oversaw its growth over the next dozen years as its sole living founder and principal funder. She took charge at a time when the nation was in the grip of a full-blown financial panic.

The federal government decided to sue the Stanford estate for more than $15 million in an attempt to recover the outstanding loans it had made to the Central Pacific Railroad—a claim that, if upheld, might have forced the estate into bankruptcy. Funds that the university had counted on to operate became entangled in a two-year legal battle and four more years of uncertainty, coinciding with a national economic depression. Those years were lean and difficult, causing Jane many sleepless nights. She paid faculty salaries out of the $10,000 monthly allowance given to her by the probate court. Ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court decided in her favor, and the probate court released the estate’s funds to her. Still in search of revenue, she even tried, unsuccessfully, to sell her jewels in London to support the struggling institution.

She soon found herself in another power struggle. She and Jordan disagreed over the university’s direction. Jane wanted to complete the construction of campus buildings, while Jordan wanted to boost faculty salaries. Looking for allies, Jane recruited the head of the university’s German department, Julius Goebel. He was scornful of Jordan and shared with Jane reports of Jordan’s alleged misdeeds—including prioritizing favoritism and loyalty over academic quality. He cited Jordan’s whitewashing of a sex scandal involving a professor within Jordan’s “clique” accused of having an “inappropriate” relationship with a young woman working at the library. According to Goebel, Jordan punished an assistant librarian who had reported the alleged misconduct, threatening him “if he did not leave California at once.”

Appalled by these reports, Jane urged fellow trustees to force Stanford’s president out of his job. On Friday, January 13, 1905, the day before the first poisoning attempt, she met with Stanford’s board in the grand, wood-paneled library of her Nob Hill mansion. The following night, someone tried to kill her.

A week later, an analysis of the spring water Jane had drunk found that it contained nux vomica, used as rat poison because it contains strychnine. Fearing for her life, Jane hid herself away at hotels. She kept a low profile—not an easy thing for one of the United States’ most famous women—until she could slip away a month later aboard a steamship bound for Oahu. Detectives were investigating the poisoning attempt, but they still hadn’t identified the culprit.

Jane, Berner, and a newly hired maid endured rough seas during the six-day passage to the islands. They reached Honolulu, where the fragrance of delicate plumeria leis greeted them from the wharf, and soon settled into their rooms at the Moana. For two decades, Berner had been Jane’s constant companion. In her 20s and recently arrived in San Francisco with her ailing mother and brother, Berner had approached Jane about employment. Her main qualification, it seems, was that she was a good listener. The two women had spent nearly every day together since—although Jane’s private secretary may have been growing weary of her wealthy employer’s frequent complaints and demands. In a reminiscence Berner wrote about her years with Jane three decades after her death, she unflatteringly details her employer’s concerns over her various health problems and hints at her frustration with being given little time off to see her own family.

On the morning of February 28, the women stepped into a horse-drawn carriage that would take them into the mountains. After a long and somewhat bumpy ride, they enjoyed a picnic on the Pali—the Hawaiian term for a cliff—where they lounged on cushions in a small grove and enjoyed the ocean views and ate hard-boiled eggs and sandwiches. Despite the mild day, Jane was dressed entirely in black, as had been her habit since the death of her only child two decades earlier. They followed their lunch with chocolates and gingerbread fresh from the hotel’s oven.

Eight hours later, just before midnight, Jane Stanford was pronounced dead. At around 4 a.m. on March 1, the Honolulu deputy sheriff convened a coroner’s jury of six in the Moana’s private dining room to view the body before it was taken to the morgue for an autopsy. One of the doctors present when Jane died sent two cables to the mainland: one to her brother, Charles G. Lathrop, and the other to her lawyer. Both cables read: “Mrs. Stanford died suddenly.” On March 4, soon after learning of Jane’s death, Jordan boarded a steamship for Hawaii, ostensibly to collect her remains. Two days later, the coroner’s jury reconvened to hear witnesses, expert testimony, and the findings of the autopsy. Berner was the first witness called, and the Pacific Commercial Advertiser described her testimony as “frank, if anything…too engagingly frank.” After three days of hearings, the jurors delivered their verdict on March 9 after just two minutes of deliberation: Jane had died “from strychnine poisoning, said strychnine having been introduced into a bottle of bicarbonate of soda with felonious intent by some person or persons to this jury unknown.”

The next day, as Jordan and his party disembarked from their steamer in Honolulu, the front page of the Advertiser trumpeted: “Mrs. Stanford Was Murdered.” Jordan immediately set out to obscure that verdict. He hired his own “expert,” a young surgeon from a prominent local family who had been in practice for only a year. For a sizable payment from Jordan, the doctor produced a four-page memo stating that Jane’s spasms might have been due to hysteria and overeating and suggesting that she died of a heart condition—not poisoning. The hired doctor never examined the body or performed his own autopsy; he had a conversation with Berner, whose account of her employer’s death began to shift after Jordan’s arrival. In a press release sent just after he boarded his steamship back to San Francisco, Jordan blamed the death on causes other than strychnine poisoning—namely, Jane’s advanced age and overexertion. He also disparaged the team of doctors in Hawaii.

Upon his return to California, newspapers such as the New York Times quoted Jordan as saying that Jane had died a “natural death.” Other accounts blamed Jane’s overindulgence in gingerbread and other treats at the picnic on the Pali. Before long, the story of her death disappeared from the papers. Jordan, meanwhile, kept his job until 1913.

This is a moment when many institutions are examining their histories—and Stanford is no exception. Last year, it convened a group of scholars, students, and eminent alums to look at Jordan’s role in the 20th-century eugenics movement. The task force’s findings revealed that Jordan, like many powerful men of the time, believed some races were genetically superior to others. He warned against the risk of “race degeneration” and spoke and wrote about the superiority of Anglo-Saxons while disparaging Black, Chinese, Mexican, Jewish, and Hawaiian people. He also held dismissive attitudes toward women, who he believed “lacked originality.”

Last October, the university announced it would rename Jordan Hall, Jordan Quad, and other structures—stripping away the honors once accorded to its first president. It took these actions because of Jordan’s role as a leading eugenicist; it did not show the same sense of anger or concern about how he treated Jane Stanford’s death. The task force glided over his cover-up of her murder with a single sentence in its 54-page report, noting that “Jordan’s relationship with Jane Stanford, by all accounts, also deteriorated over time, culminating in his controversial involvement in the aftermath of her mysterious death in 1905 in Hawaii.”

To this day, in its official online history of the university, Stanford’s administration doesn’t acknowledge that Jane died of poisoning and relegates her 12 years as the sole surviving founder to one sentence. Stanford’s communications office says that the university does “acknowledge that many questions surrounding Jane Stanford’s death remain unresolved” and that a “broader initiative” to tell Stanford’s history, including Jane Stanford’s role in it, is in the works. Laura Jones, the university’s director of heritage services and its archaeologist, says she’s often been told, while discussing the poisoning, “ ‘Oh, that’s not really proven,’ or ‘She just took patent medicine.’ I have heard it many times.”

But others are trying to solve the mystery. One author, Lulu Miller, who spent almost a decade researching her 2020 account of Jordan’s life, Why Fish Don’t Exist, believes that Jordan had the means to bring about Jane’s death. She discovered that Jordan had, in fact, used strychnine in his work collecting fish specimens. That detail, she writes, sent “a flash of heat up my neck.” While Jordan had “the timing, the motive, the access and familiarity with strychnine,” though, Miller admits she just wasn’t able to find enough evidence one way or the other to tip the scales.

Students and scholars at Stanford have also dug into the mystery. From 1995 to 2001, teams of archaeology students led by Jones began excavating a lawn that had been the site of Leland and Jane’s campus home. Among such discoveries as chamber pots and Jane’s cold cream jar, one team found a blue glass poison bottle. At the time of the dig, Jones says, the technology to test for poison residue wasn’t yet available. She doesn’t know whether there’s any relationship between the poison bottle and Jane’s death.

Meanwhile, a Stanford doctor decided to take his own look at the case. In 2003, Robert W.P. Cutler, a retired neurology professor, broke an explosive story. By closely analyzing the toxicological reports and coroner’s inquest from Hawaii, he confirmed the initial ruling that Jane had died of strychnine poisoning. Cutler finished his slim volume, The Mysterious Death of Jane Stanford, a year before his own death in April 2004. In the book, he carefully and persuasively documents how, after Jane’s death, Jordan waged a successful campaign through press releases and briefings to hide her poisoning.

Around the same time, emeritus professor W.B. Carnochan was pursuing a slightly different line of detective work. He was looking into the German professor Julius Goebel, whom Jane seems to have recruited as her informant against Jordan. Carnochan’s research confirmed a possible motive for Jane’s murder: she was contemplating, as Goebel wrote, “the final remedy…the removal of the President.”

Others, led by history professor Richard White, have joined the hunt for truth. White has offered the freshman seminar Who Killed Jane Stanford? to two groups of Stanford undergraduates. In 2014, the first group of about a dozen students searched the university’s Special Collections for clues about her death. The group convened a mock grand jury to weigh the historical evidence. Unanimously, it voted to posthumously “indict” Bertha Berner, the only person present for both poisoning attempts, for murder and David Starr Jordan for obstruction of justice.

The second group of White’s students tried again two years later, this time co-taught by Jake Warga, a journalist who was then a lecturer with the Stanford Storytelling Project, a university arts program. The class built on the research work that had been done in 2014 and produced a two-part podcast titled Who Killed Jane Stanford. It concluded with this statement from Professor Alexander Nemerov, the chair of Stanford’s Department of Art and Art History: “The official proclamations of what is remembered and what is forgotten are not to be trusted.”

Picking up where Cutler’s book and Carnochan’s research ended, White will soon publish his own volume on the subject. His work promises to reveal more insights into the crime and prompt further examination of Stanford’s early history. He may also identify Jane’s murderer.

“My literary agent insists that I do not reveal any details until publication, but I can say that [my book] centers on Jane Stanford’s death and its cover-up—both of which are tales of Gilded Age San Francisco and Stanford University. I do name a killer and explain how and why Jane Stanford died and how and why important people worked to deny she was poisoned. It is a surprising story—at least, it surprised me, and I usually consider myself hard to surprise. It takes in Chinatown, Boss Abe Ruef and San Francisco politics, spiritualism, academic politics, and elite San Francisco. Dashiell Hammett did not invent noir San Francisco out of whole cloth,” he wrote in response to my request to interview him.

Meanwhile, for at least one student in the Who Killed Jane Stanford? seminar, the bronze cast of Jordan’s head in the Special Collections library took on a sinister new meaning. Nathan Weiser, who participated in the first seminar, explains, “I remember walking by that bust of David Starr Jordan and thinking, ‘Murderer!’ ”

The mystery of who killed Jane Stanford may indeed finally be solved by White, one of the university’s brightest stars. And the institution, in turn, is finally beginning to acknowledge the key role that Jane played in its earliest years. University archaeologist Jones says she is in dialogue with the office of Stanford president Marc Tessier-Lavigne about the need to reexamine the way the university tells its origin story. “I think Jane Stanford is a very complex figure and poorly understood,” Jones says. “There is a lot of misogynistic paternalism about Jane Stanford.”

In late 2019, the university celebrated its formal renaming of a major campus landmark in Jane’s honor. It was the first time in the school’s history that she had been recognized in such a way. On October 7, 2019, Serra Mall, the university’s central gathering place and its official address, was renamed Jane Stanford Way. “It shouldn’t have taken so long,” says Catherine Pyke, author of Jane Lathrop Stanford: Mother of a University. Without Jane, “there would be no Stanford University.”

Jane’s life—and her brutal death—is the story of an intriguing woman who wielded immense economic power at the turn of the 20th century. She lost her son, cofounded a world-class university, and beat the federal government in court. She supported women’s suffrage and pushed to make the school coeducational, but she can’t be seen as a feminist hero, considering her stance against having too many female students enrolled. She ended up as a murder victim, with Jordan and others clouding the true circumstances of her death.

But why didn’t anyone demand justice for Jane? Bertha Berner, who inherited money from her, and David Starr Jordan, who held a prominent role at Stanford for 11 years after she died, both benefited from her death. And it remains a mystery why her own relatives didn’t push harder to find out what really happened.

Today, researchers are doing just that. What they unearth about Jane Stanford and her death may be as surprising as the life she lived. •

John David Mancini and Jessica Israel provided research assistance for this article.