The Citizen Scholar Who Led the Hunt for Queen Lili’uokalani’s Lost Diaries

Julia Flynn Siler on Author and Historian David W. Forbes

In April of 1957, as many students in Hawaii spent their spring breaks splashing in the gentle waters off Waikiki, a gawky, self-conscious 16-year-old named David W. Forbes headed away from the beach. He spent his break indoors in a nearly empty government building known as the Territorial Archive, where the most precious of Hawaii’s historical records were kept.

This was a time when a new craze for surfing, first pioneered by Native Hawaiians, was catching hold. Hawaii was still a US Territory. A svelte, young Elvis Presley hadn’t yet filmed Blue Hawaii. Forbes, by then, realized he was more comfortable in a library than in swim shorts. “I hated the beach,” he recalled. So the 6’1” sandy-haired teen headed indoors and began a lifelong treasure hunt that continues today.

In a fusty archive that lacked air-conditioning in 1957, the teenaged Forbes settled into a solitary routine of rifling through dusty cartons, filled with century-old documents and images. He’d requested files on a Big Island ranch famed for its paniolos, or Hawaiian cowboys. The archivists brought him carton after carton, with some documents dating back to the 1830s. He ended up spending many days there that spring, arriving when it opened at 7:45 am and staying until it closed at 4:30. “There was just so much stuff there. It just blew the top of my head off,” he recalled. “It was a whole story waiting to unfold.”

The technicolor vision of the islands that would soon colonize America’s popular imagination had little to do with the sepia-toned world that Forbes was exploring. He focused on the history of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the period when the islands were an independent constitutional monarchy that lasted from 1810 to 1893.

As the decades passed, Forbes painstakingly tracked down archival portraits of people alive in that era, in libraries and private collections throughout the islands. That set him on a half-century hunt for clues about the dynastic line of Hawaiian royals. While he’s not well known on the mainland, Forbes might be considered Hawaii’s Robert Caro.

“He’s like a walking file cabinet,” says University of Hawaii Professor Emeritus Marvin “Puakea” Nogelmeier. He believes that Forbes’s life work—the four-volume Hawaiian Bibliography and The Diaries of Queen Lili’uokalani, will be used by scholars for decades to come. Forbes’ annotation, which puts the royals’ often hard-to-read (and understand) writings into a historical context, is likely to be used by generations of future scholars who seek to understand the 19th-century world of Hawaii.

For the past ten years or so, Forbes has been on a particularly challenging quest: to reassemble the diaries of Lili’uokalani, the last Queen of Hawaii. Forbes has long known the contents of the extant fragments of Lili’uokalani’s diaries, the so-called seized papers—precious diaries, documents, and letters scooped up by her enemies in 1895 in an effort to prove she’d known of an effort to overthrow the young Republic of Hawaii. His search of the last decade has been for the missing diaries and the many unknown or hidden parts of the queen’s story.

Queen Lili’uokalani, c. 1880.

Queen Lili’uokalani, c. 1880.

This hunt proved far more difficult—and took far longer—than he ever imagined. Some diaries were simply missing, including those for the months leading up to her overthrow in 1893. Others were burned in a bonfire on the eve of the deposed queen’s arrest in 1895. Others were written in code. Some had missing pages or months or years. Often, Lili’uokalani would refer to individuals by using their initials or just their first names. Forbes’s tenacity in combing through the archives, the newspapers, and private collections, slowly, though, began to reveal a three-dimensional quality to the Queen’s often terse and guarded writings.

“She was a real person,” he told me. “Not a goddess.”

His motive for so many decades of mostly solitary work? “It was a puzzle and I like to solve puzzles,” he said.

Seventy-nine now, Forbes was born and raised in Honolulu as the adopted son of a prominent white family. He briefly attended Punahou, the independent school attended by Barack Obama, as well as Hawaii Preparatory Academy on the Big Island, and then studied history and art at the University of Hawaii. His dream was to become a painter, yet concluding he lacked the talent to succeed, he turned to archival research instead. He never affiliated with a university as an academic or pursued an advanced degree in history. His mother, Eureka Forbes, was one of the first women legislators in the state of Hawaii and was a co-founder of Hawaii Pacific University.

To his surprise, he discovered through his research that not only had his adopted grandfather been the business manager of one of the leaders of the overthrow, W. O. Smith, he’d also been the notary public who’d recorded Queen Lili’uokalani’s abdication from the throne in 1893. His grandfather, he notes, never told him about his involvement in the overthrow (Forbes was seven when he died.) Forbes only stumbled upon it many decades later by examining the original abdication document in the archives and noticing his grandfather’s name on it.

Forbes says he had a falling out with his family and did not inherit great wealth. “My father couldn’t understand why I was bothering with this old stuff,” Forbes said. “They (his father and mother) decided I was never going to turn into anything.” He added his parents would have preferred for him to have chosen a profession to “bring in the bucks.”

Over the years, Forbes worked for a leading rare bookseller at John Howell for Books in San Francisco, and consulted for a leading collector of Hawaiian books, photos, and manuscripts, Paul Kahn, a part-Hawaiian man whose collection he helped to eventually bring to the state archives. He also supported himself for many years with what he calls “crummy day jobs,” all in the interest of his love of research. He prefers not to go into specifics about what those jobs were.

He did come into some money in 1964 after recognizing five unusual paintings in the home of a Honolulu acquaintance. He scraped up the money to buy them and ended up with one of the great 19th-century treasures of the painting tradition now known as “Hawaii Volcano School”: Jules Tavernier’s “Sunset Over Diamond Head,” which he eventually sold to a private collector, who eventually sold it to the Honolulu Museum of Art. “It was fun owning a masterpiece,” he said, adding a bit wistfully, “I had it about five years.” The proceeds from selling the paintings helped ease his financial situation for a time.

While archival researchers these days employ an array of digital tools, Forbes does it the old-fashioned way: he slowly transcribes often dense and difficult-to-read 19th-century handwriting onto paper, and then later onto his MacBook. It’s his only concession to the digital age. He doesn’t have an email address or a smart phone. He doesn’t own a television. When I’ve wanted to talk to him over the years, I’ve had to call him on a landline early in the morning, before he leaves his apartment to take a bus to the archive. He doesn’t drive.

For decades, he’s had a regular seat in the reading room of the Hawaii State Archives (in the second row, closest to the State Archivists’ office) and would often wander in the late afternoons to the nearby microfiche room, in the basement of the Hawaii State Library, to pore through 19th-century newspapers. He recalls working in near solitude in the archives of the Bishop Museum during the 1960s and 70s, before there was air-conditioning.

Forbes has devoted his life to gathering historical material related to the 19th-century’s Kingdom of Hawaii—often to the bafflement of people who see him working diligently every weekday in the archives, without an apparent deadline to meet. “The word about me is that he never gets anything finished,” he said.

Royal siblings (clockwise from top left): David Kalakaua, William Pitt Leleiohoku, Miriam Likelike, and Lydia Liliu. H. L. Chase, 1874, Hawaii State Archives.

One of those endless projects seemed to be the Queen’s diaries. The effort to publish them has a bumpy and problematic history. When Forbes began exploring the archives in the 1950s, the debate over cultural appropriation of Hawaiian history hadn’t yet surfaced. By the mid-1980s, it had, as the University of Hawaii’s Hawaiian Studies program got underway. Because Forbes is a haole—a white person—from a missionary family, his work met with some skepticism among Native Hawaiian organizations. At least one balked at publishing his work and, another organization abruptly cut off his funding.

At different points along the way, the project looked doomed. He faced the same problem many scholars of Hawaiian history have faced, says Denise Noelani Arista, an associate professor at the University of Hawaii. “Underfunding and under-support.” Arista adds that “Hawaii’s place in the American imagination is where people go to drink mai tais, not a place where serious scholarship takes place.”

Forbes struggled for support until the Queen Lili’uokalani Trust stepped in. As a white person working in the archives and researching Hawaiian history as interest in Native Hawaiian studies at the University of Hawaii was surging, Forbes was largely ignored by the activists and scholars who started coming to the archives—an arrangement he says he prefers. Yet, against the backdrop of Hawaii’s conflicted history, Forbes’s race and class identity was a steep hurdle to his work’s acceptance. “He could be dismissed as just a haole scholar,” explained Nogelmeier. “But he is an amazing resource.”

Forbes’s personality didn’t help his cause. In an island state with a culture of “talk story,” which values the islands’ long, oral tradition of sitting together to swap tales, Forbes admits he’s more comfortable with books and papers than human beings. “The first time I met him, he completely ignored me,” recalls Barbara Pope, a publisher and book designer who first encountered him in the reading room of the Hawaiian Historical Society and has worked closely with Forbes for three decades. “He’s very off-putting and I just stayed out of his way. But the amazing thing about him is if you’re working together in a library, you’ll learn something from him—just by what’s he looking at, how long he’s looking at it, and what he’s pulling from the files.”

Forbes’s career, in a sense, illustrates the power of sitzfleisch, the German expression for the ability to sit for long periods of time to get things done. Forbes has that talent: for days, for years, for decades, he sat in reading rooms and libraries, quietly and methodically working his way through papers. “It was just days, weeks, months of plodding,” he said. In truth, it was years and decades.

Eventually, he did find support for his work. His decade-long project to gather and annotate Lili’uokalani’s diaries was financed by the Lili’uokalani Trust, a foundation set up in 1909 by the deposed queen to support Native Hawaiian children. Since he doesn’t read Hawaiian, he was aided in the Hawaiian language translations by University of Hawaii Professor Nogelmeier and the longtime staff translator for the Hawaii State Archives, Jason Achiu. (Most of the Queen’s writings were in English.) His publisher was the University of Hawaii Press.

About three years ago, he had a breakthrough. Ironically, it didn’t come through his archival work. Forbes had a chance conversation with the University of Hawaii professor Nogelmeier, who mentioned knowing of a family member of the queen who had a 1889 diary, who’d had that treasure tucked away on a bookshelf at home. It was a longer version of Lili’uokalani’s private diary from 1889—significantly different from the one the state archive had in its vault.

The owner of the diary, a part-Hawaiian woman named Louis Koch (Gussie) Schubert, brought the small book, with its soft leather cover and yellowed pages, wrapped in acid-free tissue, to the head of the State Archive. After the loan paperwork was signed, the archivist brought it to the table where Forbes, then 76, sat in his regular spot in the reading room.

“David? He’s a curmudgeon!” exclaims Gussie Schubert, who’d inherited the 1889 diary and had mentioned it to Nogelmeier. “I’m not a history person. I run a needlepoint shop and love needles and thread. But when you’re with David, the history comes alive,” she says, referring to his near-encyclopedic recall of Hawaiian figures from the 19th century and his uncanny ability to recollect how they’re related to their 21st-century descendants.

The discovery was important because events of 1889 remain murky to most historians, who’ve long wondered how much Lili’uokalani supported the failed coup against her brother, King Kalakaua. Piecing together all the references in the 1889 diary seemed a nearly impossible task, but because Forbes had already spent decades absorbing the characters who populated 19th-century Hawaii, he was able to fill in many—though not all—of the blanks with his annotations.

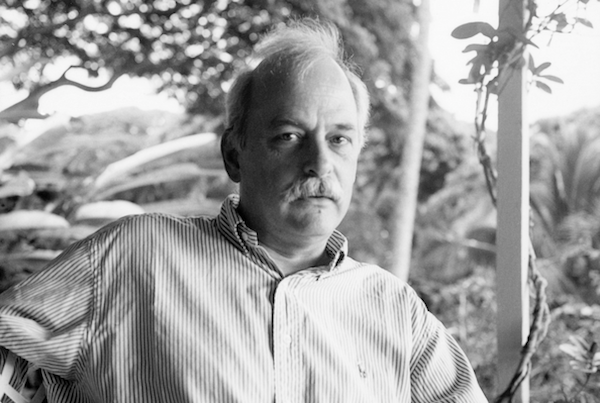

David Forbes, photo by Lynn Ann Davis.

David Forbes, photo by Lynn Ann Davis.

He was also able to document the quotidian details of Lili’uokalani’s daily life: she regularly recorded the eggs she sold to her neighbors for $1 a dozen, for instance. Her strained financial circumstances are also revealed in her entries. For example, in January of 1889, Lili’uokalani wrote in her diary that she was weighing whether to buy stock in a new railway venture and deciding whether to sell her investments in a Waimanalo sugar plantation she’d invested in. She spent much of the fall of that year planning to lease lots from one of her sub-divided properties in Waikiki, in part to pay off her debts. These entries and Forbes’s annotations underscore the extent to which Lili’uokalani was financially entangled with the American and European businessmen who would eventually overthrow her, four years later.

The diary also contains commentary about some of the most momentous episodes in Hawaiian history. In 1889, for example, Lili’uokalani not only writes about attending a Waikiki luaua with the Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson, but comments on the question about her involvement in an armed effort to overthrow her brother, King David Kalakaua, and take his place on the throne.

There are still many mysteries: Forbes wants to better understand why Lili’uokalani stopped writing in her diary in the fall of 1892.

The key question the newly published 1889 diary raises is whether Lili’uokalani, as heir apparent to her brother, the king, supported the so-called “Wilcox Rebellion” of 1889. Her diary entry of August 1, 1889 states, “Went at seven A.M. to Boat House to see King. Assured him that I had nothing to do with this insurrection.” Forbes’ footnote to that relates the account of a Bulletin reporter who asked her to respond to the rumors of her participation in the revolt. To the reporter, she also denied her involvement. These denials weren’t in the shorter version.

There are still many mysteries. Forbes wants to better understand why Lili’uokalani stopped writing in her diary in the fall of 1892, in the crucial months leading up to her ouster. “Damn it, I wish she had [continued],” Forbes said. “The world is poorer for that lapse.”

The tumultuous end of the Hawaiian Kingdom is an event that Forbes has been pondering since the late 1950s, as Hawaii became the 50th state. His quest began around the time James Michener published his blockbuster novel Hawaii, commercial jets began bringing more tourists to the islands, and Hollywood turned its gaze on a postcard version of Hawaii with swaying palms and hula skirts. Forbes largely ignored the explosion of popular interest in Hawaii and focused instead on its history.

Yet for all his decades of scholarship, Forbes is not ready to pass judgment on one of the pressing questions of 19th-century Hawaiian history: how deeply Lili’uokalani’s was involved in the failed Wilcox coup in 1889, although he notes that the leader of the insurrection had used Lili’uokalani’s home in Palama with her permission as a base beforehand… Nor, for that matter, is he prepared to draw conclusions about her role in the 1895 counterrevolution.

“That’s up to a future historian to wrestle with,” he said.