|

|

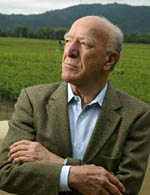

Two kings: Ian Holm as Lear and Robert Mondavi. Photo of Holm from the University of London; photo of Mondavi by Mike Kepka/SFGate.com |

|

What can Shakespeare teach us about a troubled family business?

That’s a question I’ll try to answer at a discussion hosted by a long-lasting and large book group in Burlingame, Calif., this fall. Over the summer, the group has decided to read Shakespeare’s tragedy, King Lear, alongside my book, The House of Mondavi: The Rise and Fall of an American Wine Dynasty.

To prepare myself for the evening, I’ve checked out the DVD of the Royal National Theatre’s celebrated production of King Lear with Ian Holm (which I had the great fortune to see performed in London in 1997) from our local public library. I’ve also checked out the Cliff Notes on King Lear, as well as the text of the play itself (the Pelican Shakespeare edition of the 1608 Quarto and 1632 Folio Texts).

King Lear is a heart-wrenching play that has stayed with me for years, ever since I saw Holm on a stage in London perform the storm scene, tearing off his his clothes, railing at the fates, and conveying the madness of his character with searing intensity.

Early on in my research for The House of Mondavi, I came across articles that compared Robert Mondavi to King Lear. So as I chugged north from San Francisco in my Volkswagen station wagon to the Napa Valley, I listened to BBC recordings of the play on cassettes to help try to understand the parallels.

Like King Lear, Robert Mondavi, too, was an aging king seeking to pass his kingdom onto his children. In King Lear’s case, he sought to prevent conflict at the start of the play by dividing his kingdom into three parts, to be parceled out to his three daughters, after they each declare their love for him – a so-called “love test.”

His two older daughters exaggerate their love, flattering the old king, while his youngest, Cordelia, tells him she loves him, but only as a daughter should love a father. Lear, hurt by Cordelia’s honesty, disinherits her and divides the kingdom between his two older daughters instead.

Lear quickly realizes that, in his effort to assure a smooth succession, he has, in fact, laid the groundwork for bitter enmity among his offspring and war in the kingdom. He rails against the betrayal of his daughters, uttering the famous line: “Tis sharper than a serpent’s tooth to have a thankless child.”

Running parallel to the story of King Lear and his three daughters is the story of the Earl of Gloucester and his two sons – one legitimate and the other illegitimate, and thus, disinherited.

In one sense, King Lear is a tragedy that explores the relationships between two fathers (Lear and Gloucester) and their offspring. Like The House of Mondavi, King Lear has plots and sub-plots involving betrayal and an inheritance battle. In the case of the Mondavi family, the battle involved a billion dollar global wine empire.

King Lear is also a study of king felled by hubris: It is his false pride that leads him to believe the empty flattery of his older daughters and to reject his worthy daughter, Cordelia. King Lear allows his excessive pride to destroy his family.

The House of Mondavi also explores issues of pride and hubris leading to a fall. It, too, is a tragic story, resulting in the forced sale of the family’s kingdom and long-lasting estrangement between family members.

There are plenty of differences, as well, of course. But I expect to learn a lot more after taking part in what’s sure to be a fascinating book group discussion this fall.